Blog

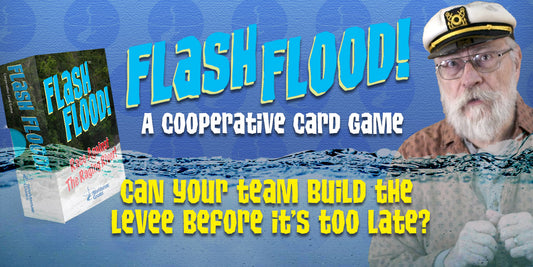

How to Play Flash Flood! (a video)

Inspired by real-world experience, this family friendly card game inspires everyone to work together to avert disaster.

How to Play Flash Flood! (a video)

Inspired by real-world experience, this family friendly card game inspires everyone to work together to avert disaster.

The new Flex Board from NewVenture!

As we expand our product line, we continually improve our production methods, seek out new sources for components, and get better at what we do! For our Peg Pastimes line...

The new Flex Board from NewVenture!

As we expand our product line, we continually improve our production methods, seek out new sources for components, and get better at what we do! For our Peg Pastimes line...

David's Top 5 Favorite Gaming Accessories

Five of my favorite accessories to enhance the game-playing experience.

David's Top 5 Favorite Gaming Accessories

Five of my favorite accessories to enhance the game-playing experience.

It's not hoarding if you have them written down!

“It’s not hoarding if you have them all written down.” Sound familiar? I have a lot of games. That is to say, “lots” of games (plural). Games of all kinds,...

It's not hoarding if you have them written down!

“It’s not hoarding if you have them all written down.” Sound familiar? I have a lot of games. That is to say, “lots” of games (plural). Games of all kinds,...

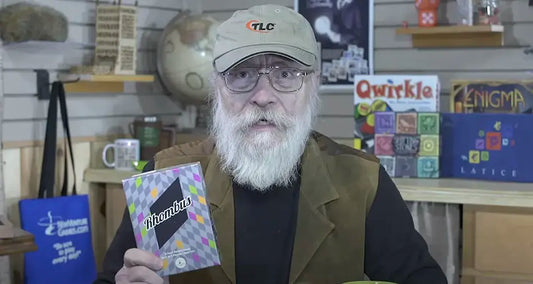

Who would've thought that Rhombuses could be so...

This is a great visual pattern-making game for the whole family. Very easy to learn and play for 2 to 6 people, or even with teams. It's simply a matter...

Who would've thought that Rhombuses could be so...

This is a great visual pattern-making game for the whole family. Very easy to learn and play for 2 to 6 people, or even with teams. It's simply a matter...